Did Marat Safin waste his talent?

Much has been said and written about former tennis champion Marat Safin over the years, with the terms "great talent" and "predestined" for success being repeated by many. However, as we shall see, this was not entirely the case.

Want to see more like this? Follow us here for daily sports news, profiles and analysis!

It seems impossible, but there was a time in the history of tennis in the 1990s and early 2000s when other players contended for the sceptre of tennis king with champions like Federer and Nadal. There weren't many of them, truth be told, but some of them seemed to have all the makings of it, and Safin was one of them.

In the men's magazine GQ, John Jeremiah Sullivan drew a powerful portrait of him in his early days, describing him as "the purest talent in the history of the game" and vehemently wondering why he had never managed to capitalise on his enormous potential. And he was certainly not the only journalist who, when speaking of Safin, combined the word "talent" with the adjective "wasted".

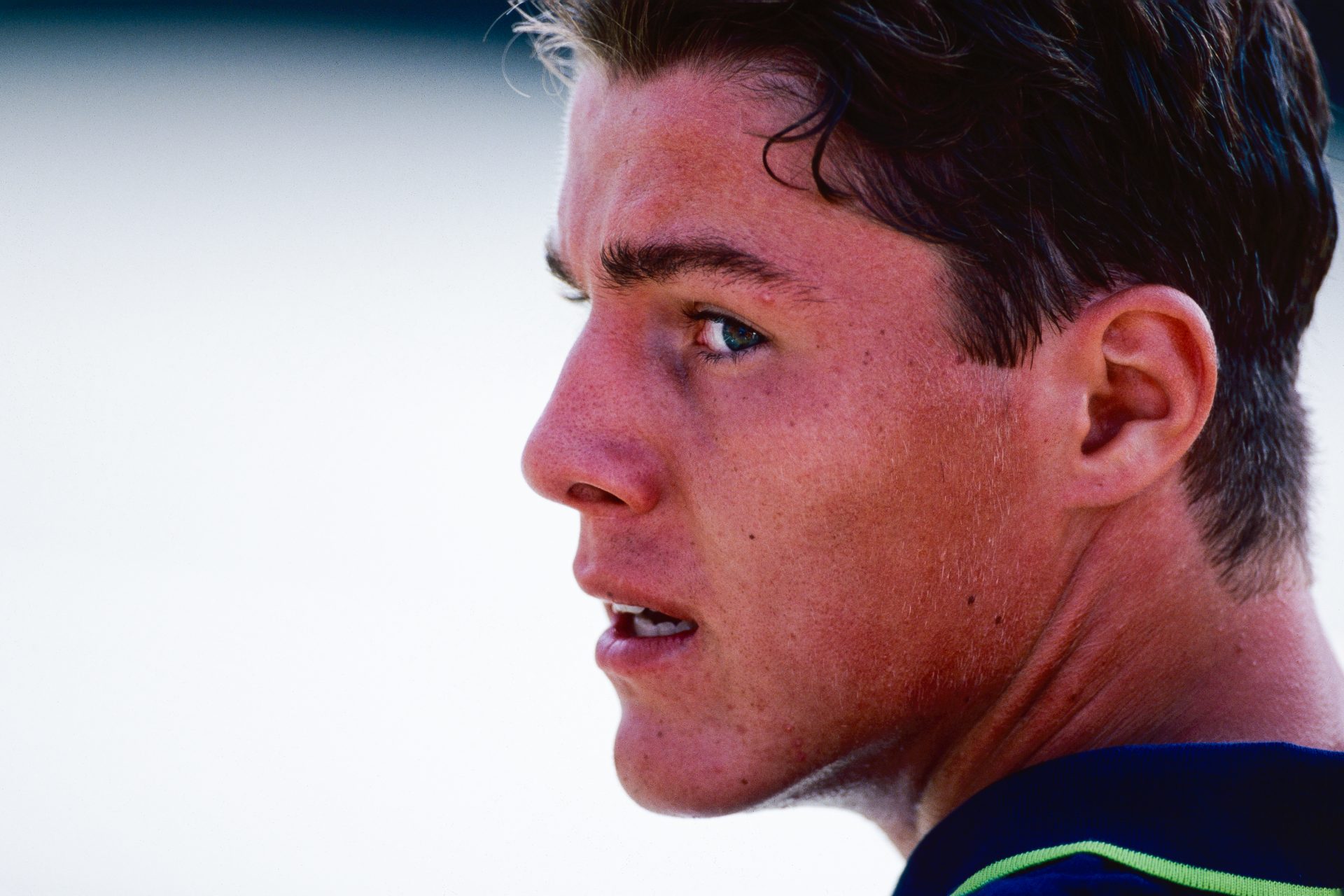

Anyone who has seen Safin play, cannot fail to remember the power of this imposing player. At 193 cm tall, he combined a powerful physique with a remarkable technical ability that became even more evident when serving, with a backhand longline (strictly two-handed) and excellent net play.

His incredible playing style was partly the result of what he learnt in his early years at the Spartak Tennis Club, the legendary Moscow club run by his father and where, over the years, some of the biggest names in Russian tennis have come from, such as Dementieva (pictured), Kournikova and Youzhny, among others.

But Safin's formation was not limited to what he learnt in his home country: also fundamental to his evolution was the training he got in Spain, a country to which he moved when he was just 14 thanks to the intercession of "a friend of a friend who wanted to do business", as La Gazzetta dello Sport reports, and who, seeing the potential of the young Marat, financed his move to Valencia.

In Spain, the very young Safin learnt to dominate the back court game, typical of 'pre-Nadal' Spanish players, but he did not disdain the net game either, and over time developed into a decidedly complete player capable of beating champions such as Andre Agassi and Gustavo Kuerten at Roland Garros in 1998, at only 18 years of age.

From that moment on, Safin began to climb the rankings quickly, winning his first tournament at the age of 19. At the time, they spoke of him as a revelation, and if anyone had any doubts at the time, he would dispel them for good the following year.

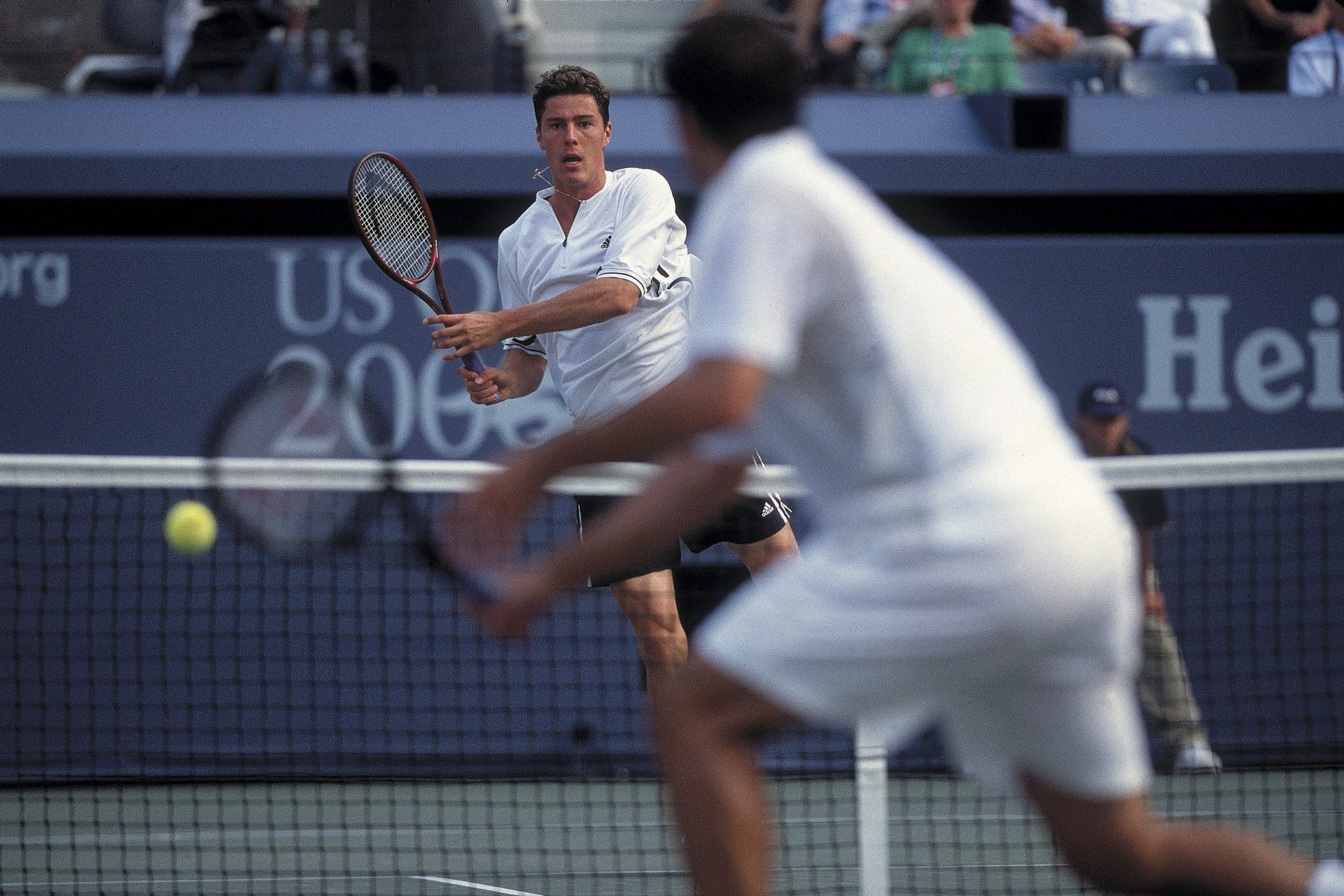

10 September 2000. A 20-year-old Safin made it to the US Open final after beating top players such as Grosjean, Ferrero, Kiefer and Martin.

On the other side of the net waiting for Safin was Pete Sampras, a man who, at that point in his career, had already won 13 majors (7 Wimbledons, 4 US Opens and 2 Australian Opens). The odds are, of course, all in the latter's favour.

Want to see more like this? Follow us here for daily sports news, profiles and analysis!

Yet Safin played his best tennis that day. The incredulous crowd watched in disbelief as the Russian defeated Sampras in just three sets (6-4, 6-3, 6-3). Safin played an almost perfect match, in which he brought home 37 winners and, most importantly, committed only 11 forced errors.

"This phenomenon played a type of tennis I didn't know, he overwhelmed me, he did what he wanted with me, like I didn't imagine, like I didn't think was possible," Sampras said in the interview at the end of the match, reported by Sports Illustrated.

Between the end of 2000 and the beginning of 2001 Safin confirmed his golden era. He won the St. Petersburg tournament and the Paris Masters and reached the top position in the ATP rankings, which he would, however, only manage to hold for nine weeks.

In 2002, he won the Paris Masters for the second time and reached the final at the Australian Open, a result he repeated in 2004. At that point, however, he began to show a certain, worrying, discontinuity in his game.

He suffered several injuries and became increasingly nervous and irritable on the court. Safin himself admitted to having smashed (deliberately and with angry gestures) an incredible number of rackets, many of them at this stage of his career. According to the BBC, he broke at least 48 in 1999 alone, while Safin told USA Today that he smashed 1055 rackets in his entire career.

If we still had doubts about the period he was going through, perhaps the words from 2002 by the New York Times can help us better understand Safin at the time, a man who "does not ease into meltdowns, he free falls into a dark alter ego that can torture him to the point where he makes the faces of a cartoon character and converses with inanimate objects."

Journalists at the time began to focus on what Safin did in his spare time and, in general, on his private life, wondering whether it was his off-court behaviour, amidst clubs, discos and love affairs, that affected his performance.

It also did not play in his favour that, between 2001 and 2004, he was losing to players who he, at other times, could have beaten with his eyes closed. Emblematic, for example, was the disastrous defeat in the final at the Australian Open in 2002 to Thomas Johansson (pictured).

Safin's performance on the court was highly unconvincing, and many attributed it to the presence in the stands of three young girls, whom the press began to call "safinettes".

Safin repeatedly found himself having to defend himself against these accusations about his private life. As reported by La Gazzetta dello Sport, the Russian said: "If you are famous, rich and frequent a fancy scene, it is not difficult to meet a beautiful girl. They talk as if women ruined me, but even when I wasn't world number one they came to my door. And yet I still won."

Yet whatever the cause of his unconvincing performances, Safin managed to rise from the ashes at the 2005 Australian Open and, just as he had done to Sampras at the US Open, win a Grand Slam by beating host Lleyton Hewitt.

In Melbourne, Safin returned to his best tennis and managed to win the final and his second major by beating Hewitt 1-6, 6-3, 6-4 and 6-4, after a semi-final (which we recommend watching again) against Roger Federer that lasted over five hours.

After the Australian Open, he was expected to make a comeback, but he appeared to be less and less interested in tennis. In 2007, nearing the Davis Cup semi-final, Safin left the Russian team, which would then lose the final against the United States at home. Safin himself, meanwhile, was in Katmandu, ready to climb Cho Oyu, the sixth highest mountain in the world.

He returned to tennis, but only briefly, until he decided to retire for good in 2009, at the age of just 29, to devote himself to politics. In 2011, he became a Duma deputy for Vladimir Putin's party and remained in the Russian parliament until his resignation in 2017.

His incursion into Russian political life was marked by his support for two of the most controversial laws promoted by the Putin government: the first was the anti-gay propaganda law (which provides for the sanctioning of anyone who exposes minors to homonormativity); the second on adoption (effectively the adoption of Russian children by US citizens).

Since leaving the Duma, Safin has, if possible, become even more withdrawn. You can see him in exhibition and veteran matches, as in the picture above, but he very rarely gives interviews and hardly uses social networks, where he alternates posts about the places he visits with nostalgic photos of Russia...alongside videos of his cats.

And when he does give interviews, Safin continues to be peremptory and somewhat elusive, as he has been throughout his career. To a Sports-ru journalist who asked him what he was doing, Safin replied laconically: "What I do? Nothing, I do nothing. I live."

Want to see more like this? Follow us here for daily sports news, profiles and analysis!

More for you

Top Stories